The Future Unfolds

The Future Unfolds

A Dialogue

Marina Caneve and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Un dialogo

Marina Caneve e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Nuove avventure sotterranee

Nuove avventure sotterranee

A Brief History of Photography in Six Images

An Essay by Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Una breve storia della fotografia in sei immagini

Un testo di Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

The Pure Image

Domingo Milella and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

La pura immagine

Una conversazione tra Domingo Milella e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Faithful Accuracy

Luca Nostri and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Una fedele esattezza

Una conversazione tra Luca Nostri e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Nautilus

Giulia Parlato and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Nautilus

Una conversazione tra Giulia Parlato e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Brisbane Songlines

Rachele Maistrello and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Brisbane Songlines

Una conversazione tra Rachele Maistrello e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Canadiana

Stefano Graziani and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Canadiana

Una conversazione tra Stefano Graziani e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Di roccia, fuochi e avventure sotterranee

Di roccia, fuochi e avventure sotterranee

Building an Image

An Essay by Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Costruire un’immagine

Un testo di Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Conceptual Traces of Geology

Fabio Barile and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Le trame concettuali della geologia

Una conversazione tra Fabio Barile e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Many Fires Burn Below The Surface

Andrea Botto and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Molti fuochi ardono sotto il suolo

Una conversazione tra Andrea Botto e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Detour In Hanoi

Francesco Neri and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Detour In Hanoi

Una conversazione tra Francesco Neri e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Hippodamus

Marina Caneve and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Ippodamo

Una conversazione tra Marina Caneve e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Martian Chronicles

Alessandro Imbriaco and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Cronache marziane

Una conversazione tra Alessandro Imbriaco e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Middle-Earth. A journey Inside Elica

Middle-Earth. A journey Inside Elica

A Conversation

Fabio Barile, Francesco Neri and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Una conversazione

Fabio Barile, Francesco Neri e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Marina Caneve and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

But a fast car and an open road can give you a sensation that’s hard to duplicate elsewhere or otherwise.1

How do you build a new technological imaginary? How do you photograph a system before it becomes reality? With her journey taking in both the Teoresi Group headquarter in Turin and the Petronas Global Research & Technology Centre in Santena, Marina Caneve invites us to explore a landscape in progress, where the future of mobility has not yet taken on a definitive shape. Her photographs seem to move within an uncertain zone, suspended between documentation and interpretation, between mapping and prophecy.

AD: Inside the Teoresi and Petronas laboratories, you have attempted to compose a geography of the invisible. Your images do not illustrate, but question. What remains of a car if we dismantle it piece by piece, until we find ourselves among gears, synthetic fluids, sensors and electronic impulses? How do you represent a distributed intelligence that has no face, but leaves only traces? What does it mean to observe a system that self-observes? In an era in which the car becomes a node of neural networks and industry becomes a feeling environment, your photographs trace a poetic cartography of a world in transition.

Marina Caneve, Laboratory, Petronas Global Research & Technology Centre, Santena, 2025

MC: The word transition is interesting because it is a concept of movement that tells us something about the dual nature of this project: it is a project that investigates the car as a means of transit and it is a project that deals with the transitions in the development of industrial processes to which the car of the future is subjected. By contrast, in the laboratories of Teoresi and Petronas, I simply tried to “be”. To look without needing to understand immediately. To slow down and glimpse what lies behind the contemporary idea of the automobile.

Photography, here, rather than describing, approaches, touches, questions and, in some way, interprets. As if each element – fluids that flow, data that passes – were part of a body that cannot be defined. I observed these structures as one studies a living and unknown organism: looking for connections, internal logic, its means of escape.

If you think about it, the great photographic campaigns have always told not what was, but what was about to be. The Mission Héliographique, officially charged with mapping French architecture, ended up building a modern idea of landscape. New Topographics, fifty years ago, recorded the beginning of a transformation that did not yet have a name. It was a matter of seeing before it was evident.

Marina Caneve, Site of an accident that occurred on December 4, 1996, 2015

Here the car has no face, but is a presence. It does not communicate, but insists. It acts as a node, as an interface, as a body in transformation. In these spaces I have never observed it as a finished object, but as a technical organism: made of tensions, exchanges, voids.

Photographing a system that self-observes implies a reversal: I was not just watching, but I was also within the gaze of the machine – this time understood as a complex apparatus, yes, but also as an industrial figure that evolves, that feels, that changes. And so the image is no longer control, but loss. Loss of a known imaginary for the conquest of a new one. As Didi-Huberman writes: “opening your eyes necessarily means making them tremble”. It is in that tremor that something is produced. Not a document. Not an explanation. A doubt, perhaps. A suspension. A landscape not yet visible, but already active. A future-present that passes through bodies, algorithms, surfaces. A partial atlas, made of interruptions and fragments, in which technique becomes a sentient space. Where not everything is understandable, but something moves, passes on. And lets itself be seen, for a moment.

AD: I have been thinking about your way of taking photographs, your artistic practice, which gathers visual data without trying to enclose everything in a narrative. The exploration of Teoresi and Petronas brought you back to this idea of open mapping, to a constellation rather than a straight line.

MC: The more time passes, the more I am convinced that photography has nothing to do with narration. If it were a matter of narration, it would imply illustrating a text or a concept with images, which would mean putting them at its service. My work is based on the exact opposite: images speak their own, autonomous language, which we must strive to understand without immediately reducing it to a linear story. “Story”, there’s another imprecise word when we talk about photography.

Marina Caneve, Photo studio, Petronas Global Research & Technology Centre, Santena, 2025

For all these reasons I feel close to the idea of open mapping, to a constellation of signs and connections that form over time, rather than to a defined trajectory. In working with Teoresi and Petronas this approach was strengthened: there was no message to describe, but a set of points to connect to build a broader and more multi-faceted vision that had as its starting point a journey into the future of the automobile. Seeing “inside” things, exploring them, questioning their meaning. Working with companies that essentially approach the same theme from different perspectives has put the focus on something that often returns in my practice: the multi-disciplinary gaze. Through discussion with experts from different fields, I have been able to build a “third” reflection, neither descriptive nor explanatory, but open, where the image does not close, but opens to the possibility of new readings.

AD: In describing the places where future mobility is being planned, you have confronted an imaginary that is still prisoner of past narratives – the automobile as a heroic body, as an extension of man, as a promise and a threat. What kind of shift in meaning have you tried to produce with respect to such a list?

MC: It’s curious that we return to the word “body”, because that’s where we started – brain and fluids – to try to think of the car no longer as an object to contemplate, but as an organism to understand.

Marina Caneve, Child’s collage, 2015

Reflecting on the imaginary to be built for this project, I thought about how traditional photography of the automotive industry has evolved. I thought about Chris Killip’s wonderful work, Pirelli Works: monochromes that sculpt bodies and gears in a darkness charged with energy, a very powerful poem that explores the relationship between man and machine in a very specific era. And then I thought about the presence of the car in the landscape and – without a doubt – the transformations of the urban landscape generated by the presence of the car. I have in mind a whole history of photography where the car is central. From the landscapes of Eggleston or Shore that are full of cars, an everyday object that does not interrupt the scene but completes it, the structure from the inside, to America by Car where Lee Friedlander brings about a profound change of meaning by using the car’s window as his frame, making the car a filter to look through. For Friedlander, the car is a visual instrument: the passenger compartment becomes a frame, an interstice through which the landscape is observed, framed, fragmented.

The shift in meaning that I have tried to make is a derivative of this operation. I have used the car as a window to show a whole series of issues that concern our time and ultimately ourselves. Years ago I created a small project in the form of an artist’s book, never exhibited and never finished, which revolved around the car as a fascination and as a threat, starting from a series of car accidents. A couple of years ago, following an accident that happened to me, I thought I would like to take up this little poem again. Well, this project does it in some way, with the body of the car on one side and with what the car sees of us, when we fall asleep while driving, for example.

AD: Compared to traditional industrial photography, your work seems to represent a rarefaction, an absence. Was it a choice or an inevitable condition?

MC: I love to approach themes without actually showing things directly, and I know this can be uncomfortable. Lateral narratives are not shortcuts: they are laborious, delicate, but necessary deviations to deconstruct those visual systems we are used to. When it comes to industrial photography, the collective imagination is still dominated by a strong, dense, masculine, almost muscular aesthetic: imposing machinery, assembly lines, hero-men who face the weight of production.

Marina Caneve, Accident in a video game, 2015

Reflecting on the imaginary to be proposed for this project, I thought about how photography, today, can tell of more rarefied, less physical, dimensions that, as you say, show something of the structures that hold things together. The rarefaction was therefore not a constraint, but a choice – even if it took shape within the very limits of access to places, of the time available, of conditions. It is a form that interests me because it opens up to a different vision space: less rhetorical, more perceptive, where things do not impose themselves, but emerge. They emerge delicate and mechanical, of a mechanical nature that, however, is not dirty with grease but dirty with pixels, sometimes exaggerated. I made an effort for this work, that of making the high-quality images of my camera dialogue with images that come from other devices, which introduce us to a dimension that is dear to me, the utilitarian dimension of photography. What purpose do the cameras that monitor us inside our cars serve?

In images with soft tones, the car is dematerialised. It does not disappear completely, but it changes its role. It is no longer the object to be glorified, but a body among others, a technical volume that acts in the landscape without necessarily dominating it. And man, too, perhaps, needs to escape from that heroic narrative.

It is curious, but while working on this project I often thought of How to do the Flowers by Ruth van Beek. In that work, the hands are cut out from DIY magazines to teach us how to do something, they are re-staged so as not to explain anything anymore, but to open up alternative universes, as in a Warburgian atlas of images. In this work, I felt the need to move from the document to the suggestion, from the demonstration to the construction of a visual landscape where the machine, the technology, the human coexist in a new form – less shouted, but perhaps more in line with how we perceive industry today: no longer as a place of the sensational gesture, but as a widespread network of presences.

AD: As in a Philip K. Dick story, we find ourselves contemplating a world in which the car not only transports us, but observes us, interprets us – monitoring our face, deciphering our body signals. How do you photograph a relationship that is now more than functional, almost symbiotic, even cognitive? How can this ambiguous zone be represented, where the car ceases to be merely an object and becomes an active component of our perceptual environment?

MC: “Whenever there are people, there are cars. And visually they blend into everything we see,” Wolfgang Tillmans tells us in the artist’s book The Cars. It is a starting point that I feel close to because it describes well a condition that is no longer exceptional, but everyday: that of a constant cohabitation between bodies and machines, in which visual differences become thinner, porous. In this shared space, photography cannot help but question the relationship – not so much the shape of the object, but its presence. The car today is no longer just a means. It is something that observes us, interprets us, anticipates us. And as in Philip K. Dick’s stories, an exchange is activated: the boundary between those who act and those who react becomes unstable.

Marina Caneve, Drowsiness detection system developed by Teoresi Group, Turin, 2025

What interests me is not showing the car, but being inside that ambiguity. Photographing the moments in which the car stops being a background and becomes an active part of our perceptive space. Working with images that do not clarify, but that open, that put into suspension. In The Cars, Tillmans does not look for the car as an iconic object: he leaves it in the flow of everyday life, confused among surfaces, shadows, reflections. It is a position that I feel close to: even if the point of view of my work on the car is completely distorted, it comes from the inside. It is about restoring the plot, not the identity. To bring out the silent but attentive presence of the constituent elements of the car, which not only transports us, but accompanies us, measures us, concerns us.

AD: In the end, perhaps what remains is not so much the idea of a defined future, but rather a kind of echo. A murmur of data, a shimmer of endlessly tested surfaces, a vague sense of acceleration with no destination.

MC: The car of the future – at least in literature and cinema – flies, talks to you, decides, accompanies you, knows you and sometimes consoles you. In Blade Runner 2049 the car is no longer just a means: it is a presence. It takes you where you need to go, but it watches you while it does so. It stays silent, or it tells you the right things. It is a bit like Samantha for Theodore in Her, it becomes more human and ends up resembling you more and more. Cinema and literature do not just tell us about an efficient car, but about a car that knows how to remain, that knows how to be there. That takes you back to someone. That doesn’t go the wrong way. That takes care of you. And perhaps all this tells us something that has little to do with the car itself but rather with the machine. The automobile of the future – the one we imagine, the one we would like – does not just tell us about technology.

“Samantha, how many people are you talking to while

you talk to me?”

“8316”

“And how many of these have you fallen in love with?”

“641. But that doesn’t diminish the love I have for you”

Spike Jonze, Her, 2013

Ultimately, photographing these places, these laboratories, these surfaces marked by anticipation, is like stretching an invisible thread between what exists and what could be. An exercise in listening, rather than seeing. As if each image, instead of fixing the future, simply grazed it, letting it flow away, in a temporary geography made of fluids, metal, impulses and lines of code. Perhaps it is right there, in that imperceptible vibration between presence and absence, that the true face of transformation lies.

1 Cormac McCarthy, The Passenger, 2022

Marina Caneve e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

But a fast car and an open road can give you a sensation that’s hard to duplicate elsewhere or otherwise.1

Come si costruisce un nuovo immaginario tecnologico? Come si fotografa un sistema prima ancora che diventi realtà? Con il suo doppio viaggio nella sede di Teoresi Group a Torino e nel Global Research & Technology Centre di Petronas a Santena, Marina Caneve ci invita a esplorare un paesaggio in divenire, dove il futuro della mobilità non ha ancora preso una forma definitiva. I suoi scatti sembrano muoversi dentro una zona incerta, sospesa tra la documentazione e l’interpretazione, tra la mappatura e la profezia.

AD: Nel cuore dei laboratori di Teoresi e Petronas, hai tentato di comporre una geografia dell’invisibile. Le tue immagini non illustrano, ma interrogano. Che cosa resta di un’automobile se la smontiamo pezzo per pezzo, fino a ritrovarci tra ingranaggi, fluidi sintetici, sensori e impulsi elettronici? Come si rappresenta un’intelligenza distribuita che non ha volto, ma solo tracce? Cosa significa osservare un sistema che si auto-osserva? In un’epoca in cui l’automobile diventa nodo di reti neurali e l’industria si fa ambiente sensibile, le tue fotografie tracciano una cartografia poetica di un mondo in transizione.

Marina Caneve, Laboratorio, Petronas Global Research & Technology Centre, Santena, 2025

MC: La parola transizione è interessante perché è un verbo di movimento che ci racconta qualcosa della duplice natura di questo progetto: è un progetto che indaga lo strumento di transito-automobile ed è un progetto che si confronta con le transizioni nello sviluppo dei processi industriali a cui l’automobile del futuro è sottoposta. Io, al contrario, dentro ai laboratori di Teoresi e Petronas, ho cercato prima di tutto di stare. Di guardare senza bisogno di capire subito. Di rallentare e di intravedere cosa sta dietro all’idea contemporanea di automobile. La fotografia, qui, più che descrivere si avvicina, tocca, interroga e, in qualche modo, interpreta. Come se ogni elemento – fluidi che scorrono, dati che passano – fosse parte di un corpo che non si lascia definire. Ho osservato queste strutture come si studia un organismo vivente e sconosciuto: cercando le connessioni, la logica interna, le sue fughe.

Se ci pensi, da sempre, le grandi campagne fotografiche non hanno raccontato ciò che era, ma ciò che stava per accadere. La Mission Héliographique, ufficialmente incaricata di mappare l’architettura francese, ha finito per costruire un’idea moderna di paesaggio. I New Topographics, cinquant’anni fa, hanno registrato l’inizio di una trasformazione che non aveva ancora un nome. Si trattava di vedere prima che fosse evidente.

Marina Caneve, Luogo di un incidente avvenuto il 4 dicembre 1996, 2015

Qui l’automobile non ha volto, ma è presenza. Non comunica, ma insiste. Agisce come nodo, come interfaccia, come corpo in trasformazione. In questi spazi l’ho osservata mai come oggetto finito, ma come organismo tecnico: fatta di tensioni, di scambi, di vuoti.

Fotografare un sistema che si auto-osserva, implica un rovesciamento: non sono stata solo a guardare, ma sono stata anche dentro allo sguardo della macchina – questa volta intesa come apparato complesso, sì, ma anche come figura industriale che evolve, che sente, che si modifica. E allora l’immagine non è più controllo, ma perdita. Perdita di un immaginario conosciuto per conquista di uno nuovo. Come scrive Didi-Huberman, “aprire gli occhi vuol dire necessariamente farli tremare”. È in quel tremore che si produce qualcosa. Non un documento. Non una spiegazione. Un dubbio, forse. Una sospensione. Un paesaggio non ancora visibile, ma già attivo. Un futuro-presente che passa attraverso corpi, algoritmi, superfici. Un atlante parziale, fatto di interruzioni e frammenti, in cui la tecnica si fa spazio sensibile. Dove non tutto è comprensibile, ma qualcosa si muove, transita. E si lascia, per un attimo, vedere.

AD: Penso al tuo modo di fotografare, alla tua pratica artistica, che accumula dati visivi senza pretendere di chiuderli in una narrazione. L’esplorazione di Teoresi e Petronas ti ha riportato a questa idea di mappatura aperta, a una costellazione piuttosto che una linea retta.

MC: Più il tempo passa, più sono convinta che la fotografia non abbia nulla a che vedere con la narrazione. Se si trattasse di narrazione questa implicherebbe illustrare un testo o un concetto con immagini, il che vorrebbe dire metterle al suo servizio. Il mio lavoro si fonda proprio sul contrario: le immagini parlano un linguaggio proprio, autonomo, che dobbiamo sforzarci di comprendere senza ricondurlo subito a un racconto lineare. Racconto, altra parola imprecisa quando parliamo di fotografia.

Marina Caneve, Studio fotografico, Petronas Global Research & Technology Centre, Santena, 2025

Per tutti questi motivi mi sento vicina all’idea di mappatura aperta, a una costellazione di segni e connessioni che si formano nel tempo, più che a una traiettoria definita. Lavorando con Teoresi e Petronas questo approccio si è rafforzato: non c’era un messaggio da descrivere, ma un insieme di punti da collegare per costruire una visione più ampia e sfaccettata che avesse come punto di partenza un viaggio nel futuro dell’automobile. Vedere “dentro” le cose, esplorarle, interrogare il loro senso. Lavorare con aziende che affrontano sostanzialmente lo stesso tema da prospettive diverse ha messo al centro qualcosa che ritorna spesso nella mia pratica: lo sguardo multidisciplinare. Attraverso il confronto con esperti di ambiti diversi, ho potuto costruire una riflessione “terza”, non descrittiva né esplicativa, ma aperta, dove l’immagine non chiude, ma apre alla possibilità di nuove letture.

AD: Nel raccontare i luoghi dove si progetta la mobilità futura, ti sei confrontata con un immaginario ancora prigioniero di narrazioni passate – l’automobile come corpo eroico, come estensione dell’uomo, come promessa e minaccia. Che tipo di slittamento di senso hai cercato di produrre rispetto a questo repertorio?

MC: È curioso che si torni alla parola “corpo”, perché proprio da lì siamo partiti – cervello e fluidi – per provare a pensare l’auto non più come oggetto da contemplare, ma come organismo da comprendere.

Marina Caneve, Collage di un bambino, 2015

Riflettendo sull’immaginario da costruire per questo progetto ho ragionato su come si sia evoluta la fotografia tradizionale dell’industria automobilistica. Ho pensato al meraviglioso lavoro di Chris Killip, Pirelli Works: monocromi che scolpiscono corpi e ingranaggi in un buio carico di energia, poesia potentissima che esplora il rapporto uomo-macchina di un’epoca molto precisa. E poi ho pensato alla presenza dell’automobile nel paesaggio e – senza dubbio – alle trasformazioni del paesaggio urbano generate dalla presenza dell’automobile. Ho in mente tutta una storia della fotografia dove l’auto è centrale. Dai paesaggi di Eggleston o Shore che pullulano di automobili, oggetto quotidiano che non interrompe la scena ma la completa, la struttura dall’interno, fino ad America by Car dove Lee Friedlander opera un cambiamento di senso profondo utilizzando la cornice del finestrino per inquadrare, facendo diventare la macchina filtro per guardare. Per Friedlander l’auto è uno strumento visivo: l’abitacolo diventa una cornice, un’intercapedine attraverso cui il paesaggio viene osservato, inquadrato, frammentato.

Lo slittamento di senso che ho cercato di operare è un derivato di questa operazione, ho usato l’auto come finestra per mostrare tutta una serie di questioni che riguardano il nostro tempo e in fin dei conti noi stessi. Anni fa ho realizzato un piccolo progetto in forma di libro d’artista, mai esposto e mai concluso, che ruotava intorno all’automobile come fascinazione e come minaccia a partire da una serie di incidenti d’auto. Un paio di anni fa, a seguito di un incidente che mi è accaduto ho pensato che mi sarebbe piaciuto riprendere questo piccolo poema.

Ecco, questo progetto in qualche modo lo fa, con il corpo della macchina da un lato e con ciò che vede la macchina di noi, quando ci addormentiamo alla guida, per esempio.

AD: Rispetto alla fotografia industriale tradizionale, il tuo lavoro sembra raccontare una rarefazione, un’assenza. È stata una scelta o una condizione inevitabile?

MC: Amo affrontare i temi senza davvero mostrare le cose direttamente, e so che questo può essere scomodo. Le narrazioni laterali non sono scorciatoie: sono deviazioni faticose, delicate, ma necessarie per destrutturare quei sistemi visivi a cui siamo abituati. Quando si parla di fotografia industriale, l’immaginario collettivo è ancora dominato da un’estetica forte, densa, mascolina, quasi muscolare: macchinari imponenti, catene di montaggio, uomini-eroi che affrontano il peso della produzione.

Marina Caneve, Incidente in un videogioco, 2015

Riflettendo sull’immaginario da proporre per questo progetto ho ragionato su come la fotografia, oggi, possa raccontare dimensioni più rarefatte, come dici, meno fisiche, che mostrino qualcosa delle strutture che tengono insieme le cose. La rarefazione quindi non è stata un vincolo, ma una scelta – anche se ha preso forma dentro ai limiti stessi dell’accesso ai luoghi, del tempo a disposizione, delle condizioni. È una forma che mi interessa perché apre a uno spazio diverso di visione: meno retorico, più percettivo, dove le cose non si impongono ma emergono. Emergono delicate e meccaniche, di una meccanica che, però, non è sporca di grasso ma sporca di pixel, talvolta estremizzati. Ho fatto uno sforzo per questo lavoro, quello di far dialogare le immagini ad alta qualità della mia macchina fotografica con immagini che vengono da dispositivi altri, che ci introducono una dimensione a me cara, la dimensione utilitaristica della fotografia. A cosa servono le camere che ci monitorano all’interno delle nostre auto?

In immagini dai toni morbidi, la macchina si smaterializza. Non scompare del tutto, ma cambia ruolo. Non è più l’oggetto da glorificare, ma un corpo tra gli altri, un volume tecnico che agisce nel paesaggio senza necessariamente dominarlo. E anche l’uomo, forse, ha bisogno di uscire da quella narrazione eroica.

È curioso, ma lavorando su questo progetto mi è tornato spesso in mente How to do the Flowers di Ruth van Beek. In quell’opera, le mani sono lì ritagliate da riviste di bricolage per insegnarci come fare qualcosa, vengono rimesse in scena in modo da non spiegare più niente, ma per aprire universi alternativi, come in un atlante per immagini warburghiano. In questo lavoro, ho sentito la necessità di spostarmi dal documento alla suggestione, dalla dimostrazione alla costruzione di un paesaggio visivo dove la macchina, la tecnologia, l’umano convivono in una forma nuova – meno urlata, ma forse più aderente a come oggi percepiamo l’industria: non più come luogo del gesto eclatante, ma come rete diffusa di presenze.

AD: Come in un racconto di Philip K. Dick, ci troviamo a contemplare un mondo in cui l’auto non solo ci trasporta, ma ci osserva, ci interpreta – monitorando il nostro volto, decifrando i nostri segnali corporei. Come si fotografa una relazione che è ormai più che funzionale, quasi simbiotica, persino cognitiva? Come si può restituire questa zona ambigua, in cui la macchina non è più solo oggetto ma parte attiva del nostro spazio percettivo?

MC: “Ogni volta che ci sono persone, ci sono macchine. E visivamente si mescolano in tutto ciò che vediamo”, ci dice Wolfgang Tillmans nel libro d’artista The Cars. È un punto di partenza che sento vicino perché descrive bene una condizione che non è più eccezionale, ma quotidiana: quella di una coabitazione costante tra corpi e macchine, in cui le differenze visive si assottigliano, si fanno porose. In questo spazio condiviso, la fotografia non può che interrogare la relazione – non tanto la forma dell’oggetto, quanto la sua presenza. L’auto oggi non è più solo un mezzo. È qualcosa che ci osserva, ci interpreta, ci anticipa. E come nei racconti di Philip K. Dick, si attiva uno scambio: il confine tra chi agisce e chi reagisce diventa instabile.

Marina Caneve, Sistema di riconoscimento della sonnolenza sviluppato da Teoresi Group, Torino, 2025

Quello che mi interessa non è mostrare la macchina, ma stare dentro quell’ambiguità. Fotografare i momenti in cui la macchina smette di essere sfondo e diventa parte attiva del nostro spazio percettivo. Lavorare con immagini che non chiariscono, ma che aprono, che mettono in sospensione. In The Cars, Tillmans non cerca l’auto come oggetto iconico: la lascia nel flusso del quotidiano, confusa tra superfici, ombre, riflessi. È una posizione che sento vicina, seppure il punto di vista del mio lavoro sulla macchina è completamente stravolto, arriva dall’interno. Si tratta di restituire l’intreccio, non l’identità. Di far emergere la presenza silenziosa ma attenta degli elementi costitutivi della macchina, che non solo ci trasporta, ma ci accompagna, ci misura, ci riguarda.

AD: Alla fine, forse, quello che rimane non è tanto l’idea di un futuro preciso, quanto una specie di eco. Un brusio di dati, un luccichio di superfici testate all’infinito, un senso vago di accelerazione senza punto d’arrivo.

MC: L’auto del futuro – perlomeno nella letteratura e nel cinema – vola, ti parla, decide, ti accompagna, ti conosce e a volte ti consola. In Blade Runner 2049 l’auto non è più solo un mezzo: è presenza. Ti porta dove devi andare, ma ti guarda mentre lo fa. Sta zitta, oppure ti dice le cose giuste. È un po’ come Samantha per Theodore in Her, si umanizza e finisce per assomigliarti sempre di più. Cinema e letteratura non ci raccontano solo di un’auto efficiente, ma di un’auto che sa restare, che sa esserci. Che ti riporta da qualcuno. Che non sbaglia strada. Che si prende cura di te. E forse tutto questo ci racconta qualcosa che ha poco a che vedere con l’automobile stessa quanto piuttosto con la macchina. L’auto del futuro – quella che immaginiamo, quella che vorremmo – non ci parla solo di tecnologia.

“Samantha ma con quante persone parli mentre

parli con me?”

“8316”

“E di quanti di questi ti sei innamorata?”

“641. Ma questo non danneggia l’amore che provo per te .”

Spike Jonze, Her, 2013

In fondo, fotografare questi luoghi, questi laboratori, queste superfici segnate dall’anticipazione, è come tendere un filo invisibile tra ciò che esiste e ciò che potrebbe essere. Un esercizio di ascolto, più che di visione. Come se ogni immagine, invece di fissare il futuro, si limitasse a sfiorarlo, lasciandolo scorrere via, in una geografia provvisoria fatta di fluidi, metallo, impulsi e linee di codice. Forse è proprio lì, in quella vibrazione impercettibile tra presenza e assenza, che si annida il vero volto della trasformazione.

1 Cormac McCarthy, The Passenger, 2022

An Essay by Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Louis Daguerre did not invent photography. In 1839 there were many similar processes for recording and fixing photographic images, and there are many pioneers in the history of photography. Yet, our natural mechanism of understanding by simplification leads us to record only a few names and dates, a few well-aligned islands in the vast ocean of complexity. And the same is true for all the developments of the photographic language. We manage to associate certain names and dates with each season of the photographic medium and forget that culture and ideas evolve more as a constant flow of intuitions and imitations, things that become thinkable because they are suddenly technically possible, and incremental contributions from who knows how many authors buried in the folds of time.

However, if we happened to look at even the smallest part of what has remained hidden, we could find an unprecedented body of images in the photographic archive of a company like Ghella, which traces all phases of the history of photography, from the second half of the 19th century to the present day. We would come across new names and dates and glimpse unexpected geographies. The succession of canons of representation over time would seem more the result of the widespread sentiment of the different eras than the invention of individual creative geniuses. And if we were to attempt to superimpose Ghella’s visual memory on the chronology of the transformations of the photographic language, we could confuse the two narratives until making them coincide.

What follows is a brief history of photography in six images. It is the story of a company, a family and one of the greatest inventions of the 19th century.

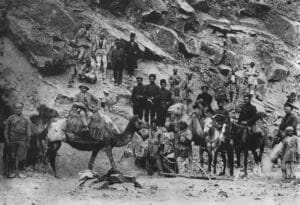

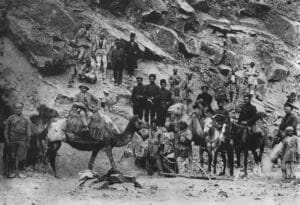

1 — The Orientalists (or Francis Frith)

In 1839, the Commission des Monuments Historiques in France realized that the fledgling medium of photography could be put at the service of archaeological exploration. Indeed, travel studies, picturesque landscapes, ancient monuments and archaeological documents formed the basis for the first photo books. The imagery captured by photographers such as Maxime Du Camp, Francis Frith and Antonio Beato were exhibited in Europe as panoramas of a glorious journey from the heroic memories of antiquity to the astonishing accomplishments of technological progress. Orientalist painting lent photography its canons of visual representation, techniques for approaching the image and a wide array of subjects that had become emblematic of a new Grand Tour.

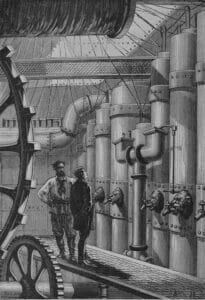

2 — The New Objectivity (or August Sander)

By the second half of the 19th century, it was already evident that photography could be used to gather knowledge and that photographic images were capable of accurately rendering reality, silencing the individual and momentary emotions that underpin every single glance. The idea of a great archive of the world suddenly seemed possible, for the mechanical eye and memory of the camera promised the absolute impartiality of the archivist. In Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts, August Sander tasks the objective eye of the lens with capturing the numerous types of humanity that characterized early 20th-century German society, fusing the notion of classification and sociological knowledge in the photographic image.

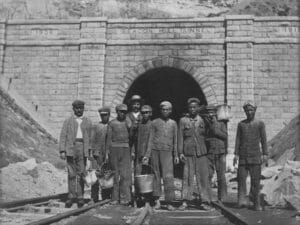

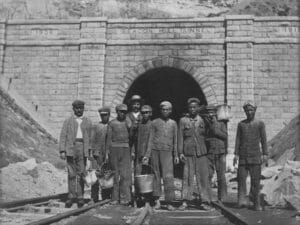

3 — The Modern Era (or Lewis Hine)

With the advent of the 20th century, photography was put at the service of both industrial advertising and political propaganda. The age of the machine and the heroic worker of the 1930s, whose heyday could be seen in the Soviet Union in the work of Alexander Rodčenko and in Germany in that of Albert Renger-Patzsch, reached its culmination in the United States with the book that the Macmillan Company commissioned from Lewis Hine. In Men at Work: Photographic Studies of Modern Men and Machines, Hine photographed workers toiling on construction sites and railways, and in machine shops, blast furnaces and mines, documenting their interactions with machines in the modern world and celebrating their contribution to shaping progress.

4 — The Documentary Style (or Walker Evans)

From the mid-1930s, the ambiguity of the photographic document became the basis for a rethinking of photography. John Szarkowski offers a good description of it: “It was at this moment that sophisticated photographers discovered the poetic uses of bare-faced facts, presented with such fastidious reserve that the quality of the picture seemed identical to that of the subject. The new style came to be called documentary. This approach to photography was most clearly defined in the work of Walker Evans.” The neutrality and detachment of these photographers from the subject results in a portrayal capable of informing as well as reflecting on our perception of the world, accepting its underlying paradox. Suddenly documentary style and art – two hitherto irreconcilable extremes – ceased to rule each other out.

5 — New Topographics (or Lewis Baltz)

In the 1970s, the vast area of work of photographers who focused on documenting the changes taking place in the contemporary landscape, in the historical shift from industrial to post-industrial economy, took shape. In 1975, the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape acknowledged that the formal and neutral detachment of the photographic document had the potential to revive our interpretative abilities, embraced the “documentary style” proposed by Walker Evans, and introduced a radical change from the traditional depiction of the landscape. Pictures of sublime natural panoramas gave way to unromantic visions of desolate industrial landscapes, suburban sprawl and everyday scenes.

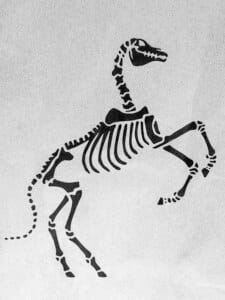

6 — The Vernacular Style (or Stephen Shore)

The recognition of colour photography as an art form is the result of a process of aesthetic emancipation that commenced in the 1970s. The first artists to take colour beyond the domain of functional or vernacular photography – terms used to distinguish artistic photographs from commercial, scientific or amateur ones – included names such as William Eggleston and Stephen Shore. Their interest in ordinary architecture and mundane aspects of American popular culture, coupled with a vaguely diaristic approach and non-hierarchical framing of the image, produced an aesthetic of colour photography based on qualities that appear to contradict their claim to be art. The vernacular, adopted as both subject and style, became the means to deconstruct and renew the rules of the photographic language.

During the same period, continual technological improvements, combined with the growing use of electronics and automation, made cameras increasingly easy to use and turned the photographer’s trade into a job accessible to everyone. The task of documenting the progress of the construction sites of companies such as Ghella started to be entrusted to anyone on site with a camera. Engineers, architects and technicians of various kinds helped to shape a new imagery of the construction site with their involuntary aesthetics. Vernacular photography – the kind without any artistic intentions, depicting ordinary events and everyday family life – entered the vocabulary of industrial photography.

Nuove avventure sotterranee (“New Underground Adventures”) brings together a selection of 32 colour images documenting infrastructures built by Ghella between the late 1960s and early 2000s (before digital photography became accessible to the general public) with the new photographic campaigns commissioned by the company between 2022 and 2023 at construction sites in Auckland, Brisbane, Buenos Aires, Naples and Vancouver.

The difference between the two groups of photographs lies in the language. The archive photographs collected in this book, shot on 35 mm film, grainy and often illuminated by artificial lights, depict the everyday life of the construction site and appear as a haphazard collection of ordinary moments, an accumulation of fragments that reflect the experience of seeing in an unfiltered manner. By contrast, the new photographic campaigns by Stefano Graziani, Rachele Maistrello, Domingo Milella, Luca Nostri and Giulia Parlato explore the same world but with greater awareness. On the one hand, due to the large amount of information condensed in each frame, on the other, thanks to each photographer’s ability to project the atmosphere of the construction site onto their personal work in an extraordinarily consistent way.

Observing the construction sites is just the starting point for a series of reflections on the clichés of depiction and the ambiguity of the photographic document, on excavation as a dreamlike interpretation of the intangible aspects of the landscape, on the symbolism of the cave and abstraction, and on the flow of the river and the depths of the sea as renderings of the city’s nature, shape and emergencies. All these factors turn their work into a contemplation of the meaning of images, reminding us once again that a photograph can be a document and an act of the imagination, a record and a possibility, all at the same time.

Un testo di Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Louis Daguerre non ha inventato la fotografia. Nel 1839 esistevano molti processi simili per registrare e fissare le immagini fotografiche e nella storia della fotografia esistono diversi pionieri. Eppure, il meccanismo di semplificazione che ci è connaturato ci porta a registrare solo alcuni nomi e alcune date, poche isole ben allineate nel vasto oceano della complessità. E lo stesso vale per le evoluzioni del linguaggio fotografico: riusciamo ad associare alcuni nomi e alcune date ad ogni stagione del mezzo fotografico e dimentichiamo che la cultura e le idee evolvono più come un flusso continuo di intuizioni e imitazioni, di cose che diventano pensabili perché improvvisamente sono tecnicamente possibili e di contributi incrementali di chissà quanti autori sommersi nelle pieghe del tempo.

Ma se ci capitasse di osservare anche una minima parte di ciò che è rimasto nascosto, potremmo scoprire nell’archivio fotografico di un’azienda come Ghella un inedito corpus di immagini che attraversa tutte le fasi della storia della fotografia, dalla seconda metà del XIX secolo fino ai nostri giorni. Incontreremmo nuovi nomi e nuove date e scorgeremmo inaspettate geografie. I canoni di rappresentazione che si sono succeduti nel tempo ci sembrerebbero più il risultato del sentire diffuso delle diverse epoche che l’invenzione di singoli geni creativi. E se tentassimo di sovrapporre la memoria visiva di Ghella alla cronologia delle trasformazioni del linguaggio fotografico, potremmo confondere le due narrazioni fino a farle coincidere.

Quella che segue è una breve storia della fotografia in sei immagini. È la storia di un’azienda, di una famiglia e di una tra le più grandi invenzioni del XIX secolo.

1 — Gli Orientalisti (o Francis Frith)

Nel 1839, in Francia, la Commission des Monuments Historiques riconosce che la neonata fotografia può essere messa al servizio dell’esplorazione archeologica. Studi di viaggio, paesaggi pittoreschi, monumenti antichi e documenti archeologici costituiscono la base dei primi libri fotografici. L’immaginario catturato da fotografi come Maxime Du Camp, Francis Frith e Antonio Beato viene mostrato in Europa come il panorama di un glorioso viaggio dalle memorie eroiche dell’antichità fino ai successi strabilianti del progresso tecnologico. La fotografia acquisisce dalla pittura orientalista codici di rappresentazione, tecniche di approccio all’immagine e un gran numero di soggetti divenuti emblematici di un nuovo Grand Tour.

2 — La Nuova Oggettività (o August Sander)

Già dalla seconda metà del XIX secolo, si comprende che la fotografia può svolgere un compito di natura conoscitiva e che le immagini fotografiche sono in grado di restituire la realtà nella sua esattezza, tacitando le emozioni individuali e momentanee che sorreggono ogni singolo sguardo. L’idea di un grande archivio del mondo sembra improvvisamente possibile perché l’occhio e la memoria meccanica della macchina fotografica promettono l’assoluta imparzialità dell’archivista. August Sander, in Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts, affida allo sguardo oggettivo dell’obiettivo il compito di rilevare i molteplici tipi di umanità che caratterizzano la società tedesca di inizio Novecento, sintetizzando nell’immagine fotografica l’idea della classificazione e della conoscenza sociologica.

3 — L’epoca moderna (o Lewis Hine)

Con l’avvento del XX secolo, la fotografia viene messa al servizio tanto della pubblicità industriale quanto della propaganda politica. L’età della macchina e del lavoratore eroico degli anni Trenta, che vede la sua apoteosi in Unione Sovietica nel lavoro di Alexander Rodčenko e in Germania in quello di Albert Renger-Patzsch, culmina negli Stati Uniti con il libro commissionato a Lewis Hine dalla Macmillan Company. In Men at Work: Photographic Studies of Modern Men and Machines, Hine fotografa operai al lavoro in officine meccaniche, cantieri di costruzioni, altiforni, ferrovie e miniere, documentando l’interazione del lavoratore con le macchine nel mondo moderno e celebrando il loro contributo alla costruzione del progresso.

4 — Lo stile documentario (o Walker Evans)

Dalla metà degli anni Trenta, l’ambiguità del documento fotografico viene posta come base per un ripensamento della fotografia. John Szarkowski ne dà una buona descrizione: “In quel periodo alcuni fotografi raffinati scoprirono l’uso poetico dei fatti guardati in modo diretto, presentati con un distacco tale che la qualità dell’immagine sembrava identica a quella del soggetto fotografato. Questo nuovo stile si fece chiamare documentario, e si è definito nel modo più chiaro nell’opera di Walker Evans”. La neutralità e il distacco di questi autori dal soggetto produce una rappresentazione capace di informare, come pure di riflettere sulla nostra percezione del mondo, accettandone il paradosso di fondo. A un tratto stile documentario e arte, due poli fino ad allora inconciliabili, smettono di escludersi.

5 — Nuovi topografici (o Lewis Baltz)

Negli anni Settanta, prende forma la vasta area di lavoro dei fotografi che si dedicano allo studio dei mutamenti in corso nel paesaggio contemporaneo, nel passaggio storico dall’economia industriale a quella post-industriale. Nel 1975, la mostra New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape riconosce al distacco formale e neutrale del documento fotografico la potenzialità di rigenerare le nostre capacità di lettura, fa suo lo stile documentario proposto da Walker Evans e introduce un cambiamento radicale rispetto alla tradizionale rappresentazione del paesaggio. Le immagini di sublimi panorami naturali lasciano il posto a visioni non romantiche di desolati paesaggi industriali, espansioni suburbane e scene quotidiane.

6 — Lo stile vernacolare (o Stephen Shore)

Il riconoscimento della fotografia a colori come forma d’arte è il risultato di un processo di emancipazione estetica iniziato negli anni Settanta. I primi artisti a portare il colore oltre il dominio della fotografia funzionale o vernacolare – termini utilizzati per distinguere le fotografie artistiche da quelle commerciali, scientifiche o amatoriali – sono autori come William Eggleston e Stephen Shore. Il loro interesse per l’architettura ordinaria e per gli aspetti banali della cultura popolare americana, insieme all’approccio vagamente diaristico e all’inquadratura non gerarchica dell’immagine, produce un’estetica della fotografia a colori a partire da qualità che sembrano contraddire la loro pretesa di essere arte. Il vernacolare, assunto sia come soggetto sia come stile, diventa il mezzo per decostruire e rinnovare le regole del linguaggio fotografico.

In quegli stessi anni, il continuo miglioramento della tecnologia, così come il sempre maggiore ricorso all’elettronica e all’automazione, rendono le fotocamere sempre più semplici da usare e trasformano il mestiere del fotografo in un lavoro alla portata di tutti. La documentazione degli stati di avanzamento dei cantieri di un’azienda come Ghella inizia a essere affidata a chiunque si trovi sul posto con una macchina fotografica. Ingegneri, architetti e tecnici di vario genere contribuiscono con la loro estetica involontaria a dar forma a un nuovo immaginario del cantiere. La fotografia vernacolare, quella priva di intenzione artistica, quella degli avvenimenti ordinari e della quotidianità in famiglia, entra nel vocabolario della fotografia industriale.

Nuove avventure sotterranee mette in dialogo una selezione di trentadue immagini a colori che documentano infrastrutture realizzate da Ghella tra la fine degli anni Sessanta e l’inizio dei Duemila (prima che la fotografia digitale divenisse accessibile al grande pubblico) con le nuove campagne fotografiche commissionate dall’azienda tra il 2022 e il 2023 nei cantieri di Auckland, Brisbane, Buenos Aires, Napoli e Vancouver.

La differenza tra i due corpus fotografici sta nel linguaggio. Le fotografie d’archivio raccolte in questo libro, scattate in 35 mm, granulose e spesso illuminate da luci artificiali, rappresentano la quotidianità del cantiere e si presentano come una raccolta disordinata di momenti qualsiasi, un accumulo di frammenti che riflettono in modo non filtrato l’esperienza del vedere. Al contrario, le nuove campagne fotografiche, realizzate da Stefano Graziani, Rachele Maistrello, Domingo Milella, Luca Nostri e Giulia Parlato, esplorano lo stesso mondo, ma con una consapevolezza aumentata. Da un lato, per la grande quantità di informazioni condensate in ogni fotogramma; dall’altro, per la capacità di ogni autore di proiettare l’atmosfera del cantiere nelle rispettive ricerche personali in modo straordinariamente organico.

L’osservazione dei cantieri è solo il punto di partenza per una serie di riflessioni sui cliché della rappresentazione e sull’ambiguità del documento fotografico, sullo scavo come lettura onirica degli aspetti intangibili del paesaggio, sul simbolismo della caverna e sull’astrazione, sullo scorrere del fiume e sulle profondità del mare come restituzioni del carattere, della forma e delle emergenze della città. Tutti questi fattori trasformano il loro lavoro in una meditazione sul senso delle immagini e ci ricordano, ancora una volta, che una fotografia può essere un documento e un atto dell’immaginazione, una registrazione e una possibilità, tutto nello stesso tempo.

Domingo Milella and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

In the necropolises of Tuscia, in the rock-hewn churches in Cappadocia, and, many years earlier, in Lascaux, I saw that there is a direct link between the cave and the spirit, as strong as that which connects the sky and the mind.1

AD: The few lines that we’ve chosen as an introduction to our conversation trace a path that sums up your line of artistic enquiry over the past twenty years with that simplicity and clarity that fill us with awe whenever we encounter our own thoughts in the words of others.

DM: I’ve been working with caves and prehistoric art for eight years. So I already had this relationship with caves and the primitive, the imagery of excavation, emptiness and darkness, before I even entered the CFT. This meant I felt at home at the consortium’s construction sites. Agamben’s words seem to look back to my past; I’ve worked extensively in Anatolia, Cappadocia, archaic Egyptian tombs, and the buried landscapes of the fringes of Aztec Mexico. I started my journey by learning to use a 20×25 view camera in the parking lots of New York’s Lower East Side in the early 2000s, but subsequently I’ve always sought something original, fresh, a first. In my final year at the School of Visual Arts I decided to skip all the Photoshop courses, devoting myself instead to colour printing in the darkroom. The transition from the colour darkroom on Manhattan’s 22nd Street to Europe’s historiated caves isn’t something that surprises me today, looking back twenty years; we all have a latent image within us, which takes its time to develop.

AD: From the caves that have preserved the oldest human traces on Earth in darkness for thousands of years to the tunnels of the new Naples-Bari high-speed railway line, which has opened underground passages in the landscape to bring contemporary humans closer to the future.

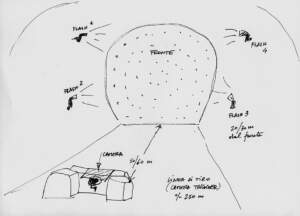

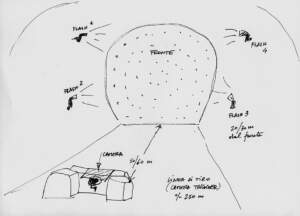

DM: The thing that strikes me most about the tunnels is the sound of the construction site, the echo of work, the undercurrent of time, of digging through time. In some of the pictures I tried to portray this sense of the depth and curvature of space and time that the tunnel conveyed. This stage of excavating the mountain, of crossing it to alter space-time, is perhaps the essence of my work, something that sucks you in and suddenly transports you far away to an unpredictable elsewhere at a crazy speed. I’ve seen the digging, the dust, the work and the sound as this collective ambition to cross the uncrossable; that’s what these tunnels do, remove us from the name, the present, the place. In the end I always arrive at abstraction.

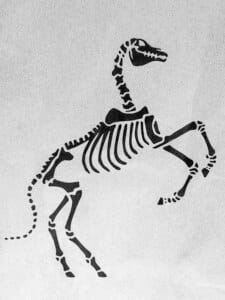

Abstract Horse, El Castillo, Spain. Courtesy of MUPAC, Santander

AD: The work collected in this book runs right through your entire imagery. In your photographs of the construction site, I saw the Hartapu monument in Kızıldağ again, the engraving of the auroch in Papasidero, the wall of the cemetery in San Giovanni Galermo and the graffiti-covered wall in Milan.

DM: I tried to make a personal work, as an artist, with the photograph itself reflected in time, curving round until its ends meet and disappearing into the concave space. That’s why clues are crucial in this puzzle, clues as images, keys to my journey – not my photographs, but the images that made them possible. There are basically two of them, then a third image, essentially forming a triangle. In May 2022, I wanted to visit the city of Benevento with my girlfriend Francesca before returning to the tunnels. I thought it was important to see the oldest city near the construction sites. Caught in a sudden downpour, we took shelter under Trajan’s Arch in the city centre. While we were under the arch, I discovered a strange, faint engraving of a horse, which was very delicate and beautiful, and I decided to photograph it with the big view camera – the camera was bigger than the drawing itself. It was undoubtedly an historical engraving, from perhaps 100, 200, 300 or even 1,000 years ago, who knows? But never mind its archaeological value, let’s return to the pure image: an arch that creates an imaginary bridge, in which, in its innermost part, there resides an animal, a Spiritus Rector, a guardian of the arch or, as they say in Ghostbusters, a gatekeeper. It was perhaps only a year later, towards the end of my visits to the CFT, that I discovered that there’s a rampant horse on all the workers’ placemats in the canteen. Actually, it’s much more than a horse, it’s the skeleton of a rampant horse. Perhaps it’s the protective spirit of the tunnel, the workers and the construction site that tries to pierce space and time like my photographs? A rampant horse also adorns the cutlery holder, containing the utensils to feed the consortium’s entire workforce; it’s dead – a skeleton – but it always resurrects, at lunch and dinner each day. We are left with the simple truth of the image: a horse that comes to life and bolts from the world of the dead, from the underworld to us. I’d seen a similar horse in Harry Potter, and it was also winged! It was invisible to everyone except Harry and his friend Luna, endowed with a strange ability to see ghosts, just like Harry, who was also initiated into mysteries that are forbidden to us. In between visits to the CFT, I also happened to have the good fortune to return to a cave I know very well, at Monte Castillo in northern Spain. It’s a triangular mountain that’s home to numerous caves, engravings, drawings and depictions of the earliest images in human history. I had been to Monte Castillo many times, but on this visit accompanied by Eduardo and Francesca we reached the point in the cave where I was convinced it ended. It’s a special, very deep place, where the stalactites and stalagmites are almost completely soaked in red ochre and where it really seems you can’t go any further beyond a precipice and a ditch. However, that day I discovered that there’s a little path that goes a few dozen metres further, and that it’s not the end of the cave; the end isn’t the real end. I also discovered that there are small carvings on the floor like nowhere else in the cave, a drawing of a pair of horses, and a lone horse at the end of the space, at the end of time.

Thestral, CFT canteen, 2023

AD: Reflection on the depiction of the construction site gradually overlapped with reflection on photography. To use Agamben’s words, that direct link that mysteriously connects the cave to the spirit, and the sky to the mind, led you from the symbolism of the cave to pure abstraction. A transition that’s also marked by the use of your phone camera as a visual notebook. It’s probably a kind of liberation after all these years in the darkness of the darkroom.

DM: Working in the darkness of caves so close to 40,000-year-old drawings has certainly changed something inside me. The complete lack of movement, the compression and the difficulties of the view camera that I’d imposed on myself in the caves, made my language abstract. The prehistoric experience liberated me from myself, putting me in touch with a bigger picture. I have hundreds of photographs taken with my iPhone that don’t depict anything… or so it would seem. In a way, they gathered themselves, as preparatory images of a highly imaginative organism. It all happened listening to music and walking in the contemporary world with the prehistoric images still in my heart. I asked myself what the future image might be? The deep past prompted me to imagine our future. I started to make room for simple signs and colours, lines and flashes on walls, surfaces, doors, boundaries of many realities. I see many of these files as “preparatory drawings”, like a game. Photography can be drawing, it can be painting, it can be what it is: Pure Image.

Domingo Milella, Il Velo sulla Realtà, self-portrait at the CFT, 2023

AD: Beneath the artificial light of the tunnel, you managed to connect two seemingly distant sides of photography: documentation on the one hand and abstraction on the other.

DM: Everything is curved and connected by a tunnel that, like a circle, reminds us that we live on the surface of a burning sphere, covered with water and earth, which floats in the darkness and moves in the light.

1 Giorgio Agamben, Quel che ho visto, udito, appreso… (Turin: Einaudi, 2022).

Una conversazione tra Domingo Milella e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Nelle necropoli della Tuscia, nelle chiese scavate nella roccia in Cappadocia e, molti anni prima, a Lascaux ho visto che fra la caverna e lo spirito vi è un nesso immediato, altrettanto forte di quello che unisce il cielo alla mente.1

AD: Le poche righe che abbiamo scelto come introduzione alla nostra conversazione tracciano una parabola che sintetizza la tua ricerca artistica negli ultimi venti’anni con quella semplicità e quella chiarezza che ci riempiono di stupore ogni volta che incontriamo i nostri pensieri nelle parole di altri.

DM: Sono otto anni che mi occupo di caverne e arte preistorica. Quindi questo rapporto con la grotta e con il primitivo, l’immaginario dello scavo, del vuoto e del buio, mi apparteneva già prima di entrare al CFT. Nei cantieri del consorzio mi sono quindi sentito a casa. Le parole di Agamben sono retro-veggenti a modo loro; ho lavorato molto in Anatolia, in Cappadocia, nelle tombe dell’Egitto arcaico, nei paesaggi sepolti delle periferie del Messico Azteco. Ho iniziato il mio viaggio imparando a usare il banco ottico 20×25 nei parcheggi del Lower East Side a New York nei primi anni Duemila, ma poi ho sempre cercato qualcosa di originario, di primo, di sorgivo. Decisi nel mio ultimo anno alla School of Visual Arts di saltare tutti i corsi di Photoshop e d’immergermi invece nella stampa a colori in camera oscura. Il passaggio dalla “color dark-room” sulla ventiduesima strada a Manhattan alle grotte istoriate d’Europa non è una cosa che oggi, ripensando a vent’anni fa, mi sorprende; tutti abbiamo un’immagine latente dentro di noi, che richiede il suo tempo per svilupparsi.

AD: Dalle caverne che hanno custodito per migliaia di anni nell’oscurità le più antiche tracce dell’uomo sulla Terra ai tunnel della nuova linea ferroviaria ad alta velocità Napoli-Bari, che aprendo varchi sotterranei nel paesaggio, avvicinano l’uomo di oggi al futuro.

DM: La cosa che mi colpisce di più dei tunnel è il suono del cantiere, l’eco del lavoro, il sottofondo del tempo, dello scavo nel tempo. In alcune immagini ho provato a ritrarre questo senso del profondo e della curvatura dello spazio e del tempo che la galleria trasmetteva. Questo stadio dello scavare la montagna, di attraversarla per modificare lo spazio-tempo, forse è il nocciolo del mio lavoro, qualcosa che ti risucchia e improvvisamente ti trasporta lontanissimo e in un’imprevedibile altrove a una velocità senza senso. Ho visto lo scavo, la polvere, il lavoro e il suono come questa collettiva ambizione di travalicare l’intravalicabile… magari è una parola che non esiste neanche, ecco cosa fanno questi tunnel: portano fuori dal nome, dal presente, dal dove. Alla fine approdo sempre all’astrazione, che mi sono spesso domandato, è azione delle stelle?!

Astratto, El Castillo, Spagna. Courtesy MUPAC, Santander

AD: Il lavoro raccolto in questo libro ripercorre trasversalmente tutto il tuo immaginario. Nelle tue fotografie del cantiere ho rivisto il monumento di Hartapu a Kızıldağ e l’incisione del Bove Primigenio di Papasidero, ho rivisto il muro di cinta del cimitero di San Giovanni Galermo e la parete ricoperta di graffiti a Milano.

DM: Ho provato a fare un lavoro personale, come artista, che con la fotografia si riflettesse nel tempo curvandosi sino a fermarsi su sé stesso e a scomparire nello spazio concavo. Per questo sono cruciali gli indizi in questo enigma, indizi come immagini, chiavi del mio viaggio – non le mie fotografie, ma le immagini che le hanno rese possibili. Sono essenzialmente due, poi una terza immagine, a formare fondamentalmente un triangolo. A Maggio del 2022 prima di tornare nei tunnel ho voluto visitare con la mia fidanzata Francesca la città di Benevento. Trovavo fosse importante vedere il centro più antico vicino ai cantieri. A causa di una grande pioggia improvvisa ci siamo riparati sotto l’arco di Traiano che si trova al centro della cittadina. Mentre eravamo lì sotto ho scoperto una strana e pallida incisione di un cavallo, molto bella, molto leggera, ed ho deciso di fotografarla con il grande banco ottico – la macchina fotografica era più grande del disegno stesso. Un’incisione storica certo, di forse 100, 200, 300 o anche 1.000 anni fa, chi lo sa? Ma non importa il suo valore archeologico, torniamo all’immagine pura: un arco che crea un ponte immaginario, dentro il quale, parte più intima, risiede un animale, uno Spiritus Rector, un guardiano dell’arco, o come dicono in Ghostbuster, un guardiano di porta… Forse solo un anno dopo, verso la fine delle mie visite al CFT scopro che sulla tovaglietta della mensa di tutti i lavoratori è impresso un cavallo – rampante. Per essere esatti, è molto di più di un cavallo: è lo scheletro di un cavallo rampante. Forse l’anima protettrice del tunnel, dei lavoratori e del cantiere che tenta, come le mie fotografie, di perforare lo spazio e il tempo? Un cavallo rampante adorna anche il contenitore delle posate, strumenti per la nutrizione di tutta la manodopera del consorzio; è morto, è uno scheletro, ma risuscita sempre, ogni giorno, a pranzo e a cena. Rimaniamo con la semplice verità dell’immagine: è un cavallo che giunge vivo e imbizzarrito dal mondo dei morti, dal sottomondo a noi. Avevo visto un cavallo simile in Harry Potter, peraltro era alato! Era invisibile a tutti, tranne ad Harry e alla sua amica Luna, anch’essa dotata di una strana capacità di vedere i fantasmi, proprio come Harry, iniziato anche lui a Misteri a noi preclusi. Tra una visita e l’altra al CFT mi capita di avere la fortuna di tornare in una grotta che conosco molto bene, al monte Castillo nel nord della Spagna. Una montagna triangolare che contiene numerose grotte, incisioni, disegni e rappresentazioni delle prime immagini della storia dell’uomo. Ero stato tante volte al Castillo, ma in occasione di questa visita in compagnia di Eduardo e Francesca arriviamo nel punto in cui ero convinto che la caverna finisse. È un luogo particolare, molto profondo, dove le stalattiti e le stalagmiti sono quasi completamente imbevute di ocra rossa e dove oltre un dirupo e un fosso sembra davvero non si possa andare avanti. Invece scopro quel giorno che esiste un piccolo sentiero che prosegue per altre decine di metri e che la fine della caverna non è quella; la fine non è la vera fine. Scopro inoltre che come in nessun’altra parte della grotta, esistono delle piccole incisioni sul pavimento: un disegno di una coppia di cavalli – e un cavallo solitario al fondo dello spazio, al fondo del tempo.

Thestral, Mensa del CFT, 2023

AD: La riflessione sulla rappresentazione del cantiere si è progressivamente sovrapposta alla riflessione sulla fotografia. Per dirla con le parole di Agamben, quel nesso immediato che misteriosamente unisce la caverna allo spirito e il cielo alla mente ti ha condotto dal simbolismo della grotta alla pura astrazione. Un passaggio segnato anche dall’uso della fotocamera del telefono come quaderno di appunti visivi. Probabilmente una sorta di liberazione dopo tutti questi anni nell’oscurità della camera oscura.

DM: Sicuramente l’aver lavorato nel buio delle grotte così vicino a disegni di 40.000 anni fa, ha cambiato qualcosa dentro di me. La totale mancanza di movimento, la compressione e le difficoltà del banco ottico che mi ero imposto di usare nelle caverne, hanno reso astratto il mio linguaggio. L’esperienza preistorica mi ha liberato da me stesso, mettendomi in contatto con un disegno più grande. Ho centinaia di fotografie fatte con l’iPhone che non ritraggono nulla… o almeno così sembrerebbe. In un certo senso, si sono raccolte da sole, come immagini preparatorie di un organismo immaginifico. Tutto è avvenuto ascoltando la musica e camminando nel mondo contemporaneo con ancora le immagini preistoriche nel cuore. Mi domandavo: quale potrebbe essere l’immagine futura? Il profondo passato mi ha spinto a immaginare il nostro avvenire. Ho cominciato a dare spazio a semplici segni e colori, linee e bagliori su muri, superfici, porte, confini di tante realtà. Molti di questi file li vedo come “disegni preparatori”. La Fotografia può essere disegno, può essere dipinto, può essere quel che è: Immagine Pura.

Domingo Milella, Il Velo sulla Realtà, autoritratto al CFT, 2023

AD: Sotto la luce artificiale del tunnel, sei riuscito a collegare due versanti apparentemente lontani della fotografia: da un lato la documentazione e dall’altro l’astrazione.

DM: Tutto è curvo e collegato da un tunnel che, come un cerchio, ci ricorda che viviamo sulla superficie di una sfera rovente, coperta di acqua e terra, che fluttua nel buio e si muove nella luce.

1 Giorgio Agamben, Quel che ho visto, udito, appreso…, Einaudi, Torino 2022.

Luca Nostri and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

AD: Unlike the construction sites visited by the other authors featured in this collection, work on the Matanza-Riachuelo Basin, one of the most complex wastewater purification projects in the world, was almost finished when you arrived in Buenos Aires. The new network of tunnels had been completed and the main wells were about to be sealed. Travelling along the banks of the Rio Matanza-Riachuelo to its mouth in the Rio de la Plata, between the barrio of La Boca and the town of Dock Sud, was the only way to “see” the invisible infrastructure that will improve the quality of life of over 14 million people in the coming years.

LN: When I was assigned the Buenos Aires construction site, I was immediately struck by the imagery of the Riachuelo River, which runs through the city and flows into the Rio de La Plata, opposite Uruguay, and which is unfortunately mainly known for its pollution and associated problems, with serious consequences for the inhabitants of some of the city’s critical districts. I have always been interested in the geographical and topographical exploration of an area, which limits my work but also helps to guide it, and is usually a good excuse to go out and take photographs. With this in mind, I started by looking back over some books, including The Red River by Jem Southam, who was my tutor at Plymouth for my PhD. Although The Red River is set in a rural area, there are many similarities in the sequence of 50 photographs following a watercourse in west Cornwall, from source to sea, which passes through different areas. The entire river valley has been extensively mined for tin and copper ore for hundreds of years, and it is the extraction of water from the mine and its use to crush the ore that stains the river red. It is also a work that combines views of the river with interiors of houses and photographs of the villages the river flows through. I have also used this strategy of photographing both the river and the inhabited areas near it.

AD: Exploring a bookshelf is the best first step of any journey. On mine, I found some passages that remind me of your way of taking photographs in a book by Robert Adams entitled Along Some Rivers: Photographs and Conversations. In particular, in the transcript of his opening speech at a debate held at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco, Adams mentions the two qualities he always looks for in people and in the art they create, collect or admire: a sense of urgency and faithful accuracy. Faithfulness (often in contrast to originality) seems to me a possible key to your work.

LN: Along Some Rivers is a book of some of Adams’s conversations with various curators and includes a largely unpublished sequence of 28 photographs along the Rio Grande and Columbia River, following human traces in the landscape. When Robert Adams talks about faithfulness, or the search for some form of truth, he’s not talking about merely descriptive, or topographical, accuracy of the real world. The goal, he says, “is to face facts but to find a basis for hope. To try for alchemy”. It’s another way of rephrasing one of his most famous and much-quoted statements: “Landscape pictures can offer us, I think, three verities — geography, autobiography and metaphor. Geography is, if taken alone, sometimes boring; autobiography is frequently trivial; and metaphor can be dubious. But taken together… the three kinds of information strengthen each other and reinforce what we all work to keep intact — an affection for life.” This “alchemy” is of course sometimes achieved and sometimes not, but it is certainly a very inspiring approach. What I appreciate about Adams’s essays and interviews is that they are unencumbered by postmodern attitudes and theorizing, and each time I pick them up they make me want to take photographs. I realize now, flipping through Along Some Rivers, that Adams’s photographs are all vertical and in hindsight, perhaps, I should have done the same.

Carleton E. Watkins Multnomah Falls, Columbia River, 1867

AD: The vertical format of Adams’s photographs allows us to introduce a distinctive aspect of your book: the orientation of the pictures in the sequence is always vertical regardless of the orientation of their subjects.

LN: The Columbia River is the same river photographed by Carleton E. Watkins in Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon, one of my reference works. The crystal clarity of the photographs is impressive. There is a very beautiful and now hard-to-find book of this work from which I took the idea of “turning the photographs” for the final sequence: the format of the book is in fact horizontal, as are almost all the photographs, but the final sequence ends with four vertical landscapes – the silhouette of a mountain on a lake and three waterfalls – that are laid out on the page. The visual transition from horizontal to vertical, playing on the horizon line, is very subtle and delicate, but also very powerful, offering the opportunity for a more abstract and formal interpretation of the photographs. This idea inspired me to construct the sequence, considering the necessarily vertical format of the book. One of the things that struck me, arriving at the site of the sole well still open, was its size, in terms of both diameter and depth. The sensation of dizziness was very strong. Additionally, due to the depth and the black concrete blocks, on a normal sunny day the contrast of light between the illuminated part, and deep part in shadow, is too high and the film is unable to record both extremes. This is the reason why the line of the well, which in some photographs I have kept very high up in the shot, becomes a kind of horizon of photographic events, below which there is a kind of total darkness, an abyss. The idea of “rotating” the image on the page by placing it vertically was also to elicit or reinforce the sensation of dizziness.

AD: Let’s resume our back and forth of books.

LN: Another book that I think is very important, although little known, is The Subdury River: A Celebration by Frank Gohlke, published in 1993. It resonates with me because Gohlke uses the 13×18 colour format, which I also use a lot. The work has a biographical basis, for the photographer takes an interest in the river near his new home after moving to Massachusetts, setting in motion that process of discovery and creation through which we come to feel at home in our own particular parts of the world. In some ways I too, as a visiting outsider, used the Riachuelo to get to know Buenos Aires, instead of starting with the city’s “highlights” as a normal tourist would. And despite being “foreign” to the city, I sought an intimate viewpoint with certain areas of the river that I’d insisted on, rather than pursuing the visuals and modus operandi of the epic exotic journey. That’s why another reference I had in mind was Fiume (River) by Guido Guidi.

Luca Nostri, View of my parents’ house at the height of the flood, Solarolo (Province of Ravenna), May 2023

AD: Fiume is a compilation of a series of shots of the river that flows a few hundred metres from Guidi’s home in Cesena. The relationship with the everyday landscape, with that area that begins immediately beyond his doorstep, reminds us of the Senio and Santerno rivers that flooded the town and countryside of Lugo, one of the municipalities most affected by the floods in Emilia Romagna, where you grew up and where your family also lives.

LN: The flooding in Emilia-Romagna last May was as shocking as it was unexpected. I was at my grandparents’ house the morning it happened, and I’ll never forget the sight of the water slowly crossing the threshold. And the water as far as the eye could see across the open, flat landscape. The reasons for the floods are complex and manifold; certainly there were a number of concurrent unfortunate circumstances, and some have spoken of a “perfect storm”, but one of the main issues is undoubtedly the management of the rivers, riverbanks and land. This brings us directly back to the work on the Ghella construction site to relieve the Riachuelo river, which is at constant risk of flooding in certain neighbourhoods: as you said at the beginning, it’s a project that is as useful as it is invisible. I’m reminded of a comment by the painter and writer Christopher Neve in a book entitled Unquiet Landscapes (recently recommended to me by my friend John Spinks) about the painter John Nash, whose method of working could be compared to that of a water-diviner who “does not actually alter anything but who has some odd quality, that enables him to hint at what may be hidden, just by looking for places and objects which carried for him a particular charge”. After all, even good photography is a kind of perfect storm.

Una conversazione tra Luca Nostri e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

AD: A differenza dei cantieri visitati dagli altri autori coinvolti in questa raccolta, il cantiere del bacino Matanza-Riachuelo, uno dei progetti di depurazione di acque reflue più complessi al mondo, al tuo arrivo a Buenos Aires era ormai quasi concluso. La nuova rete di tunnel era stata completata e i pozzi principali stavano per essere sigillati. Percorrere le sponde del Rio Matanza-Riachuelo fino alla sua foce nel Rio de la Plata, tra il barrio di La Boca e la città di Dock Sud, era l’unico modo per “vedere” un’infrastruttura invisibile che nei prossimi anni migliorerà la qualità di vita di oltre 14 milioni di persone.

LN: Quando mi è stato affidato il cantiere di Buenos Aires sono subito rimasto colpito dall’immaginario del fiume Riachuelo, che attraversa la città e sbocca sul Rio de La Plata, di fronte all’Uruguay, e che purtroppo è noto per lo più per problemi legati all’inquinamento, con gravi conseguenze sugli abitanti di alcuni quartieri critici della città. Mi è sempre interessata l’esplorazione geografica e topografica di un territorio, che mette dei confini al lavoro ma anche aiuta a pilotarlo, ed è di solito un’ottima scusa per uscire a fotografare. Con queste premesse, sono partito riguardando alcuni libri, tra cui The Red River di Jem Southam, che è stato mio tutor a Plymouth per il PhD. The Red River è ambientato in un territorio rurale, ma i punti di contatto sono molti: una sequenza di cinquanta fotografie che segue un corso d’acqua nell’ovest della Cornovaglia, dalla sorgente al mare, e che attraversa aree di diversa natura. L’intera valle del fiume è stata ampiamente sfruttata per centinaia di anni al fine di estrarne stagno e rame, e sono stati appunto l’estrazione dell’acqua dalla miniera e il suo utilizzo per frantumare il minerale a macchiare il fiume di rosso. Inoltre è un lavoro che mette insieme vedute del fiume, interni delle case e fotografie dei paesi attraversati dal fiume. Ho utilizzato anche’io la strategia di fotografare sia il fiume che le zone abitate nei suoi pressi.